So long old packet! You got me out here but I’ll be billy-be-cursed if I ever want to ride, scrub, sleep, work, or stand watch on you again.

-Attributed to Pvt Fred Leach, Co H. 4th Marines, Shanghai, China, after traveling aboard the USS Henderson

If there is one experience common to all China Marines, each started his China-side cruise by crossing an ocean. This section highlights the method, routes and ships that brought the Marines to China. It also illustrates how they viewed the voyage by utilizing their personnel observations, and augmented by artifacts. Some trans-Pacific voyages were pleasant and relaxing; others were miserable, marred by tales of overcrowding, water shortages and ships filled with the stench of vomit from scores of seasick men.

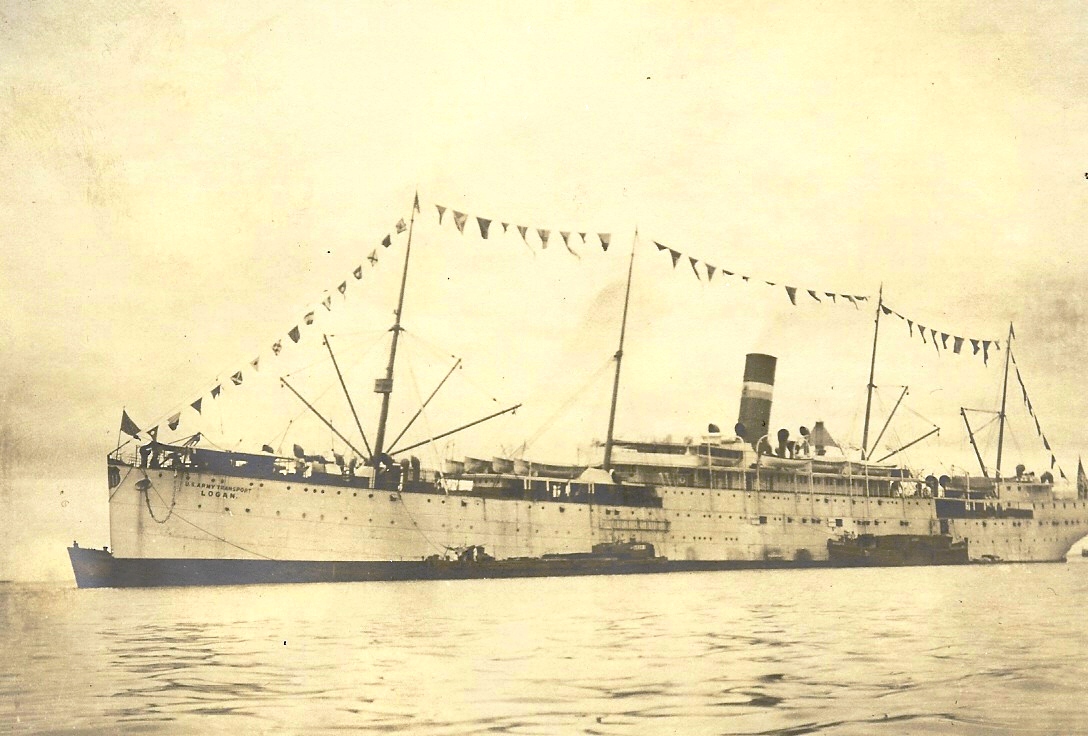

Prior to the Spanish-American War, the United States did not maintain any permanent garrison beyond its shores. Therefore, no troop transport system was in place. Any Marine serving on the China Station prior to 1898 would have reached Asia as part of a warship's crew. After the Spanish-American War the situation changed when the United States made a commitment to maintain a large garrison in the Philippines. With the US Navy also establishing bases in the Philippines, the Marines soon found themselves posted to these islands in large numbers. In fact, it was from the Philippines that the first permanent detachment of Peking-bound China Marines was drawn. Between the end of the Spanish-American War and the early 1920’s the majority of Marines heading east utilized the US Army Transport system -- a series of Army maintained transports that moved soldiers and Marines from San Francisco through Hawaii and onto Manila. Ships associated with these early Pacific runs included the USAT Grant, USAT Logan, USAT Sherman, USAT Thomas and USAT Sheridan. Once in Manila it was the responsibility of the Navy to move the Marines on the next leg of their journey to China. The Navy usually chose to transport them by either naval warship or smaller transports, such as the USS Abardenda or USS Rainbow operating out of naval bases at Olongapo or Cavite.

USAT Logan

Marines, Sailors and Soldiers departing San Francisco for the Far East

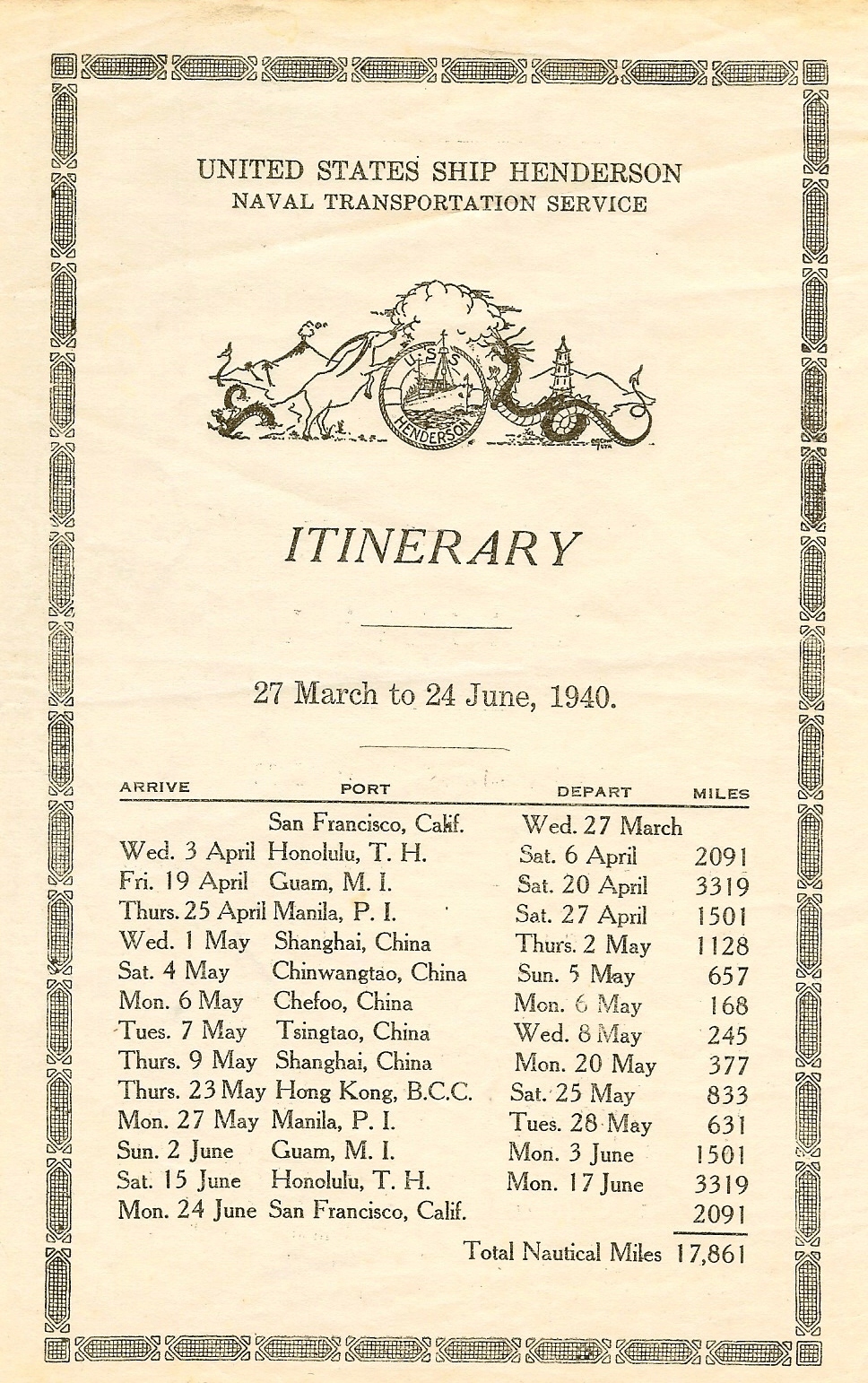

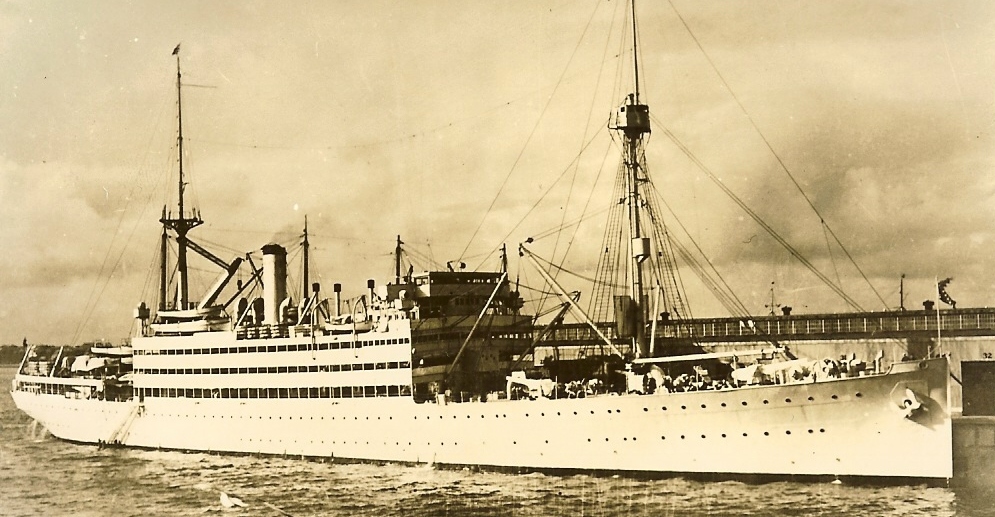

Several years after World War I, the methodology used to move Marines east changed. The Navy made available two transports, the popular USS Henderson, or “Hendy Maru” and the less popular USS Chaumont. A normal cruise for these ships would start at Hampton Roads, Virginia, run down the east coast, transit the Panama Canal, and swing up the west coast to Mare Island. Marines were picked up and dropped off at navy bases along the way. Once at Mare Island, the transports set off with a new draft of Asiatic Marines headed across the Pacific for Hawaii, Guam, and Manila. Following Manila, the ships would then turn northwest and make stops along the Chinese coast at Shanghai, Chefoo and Chinwangtao, before returning to the United States following the reverse of the route in which they came. The Pacific portion of a US Naval transport crossing would normally take about one month, and each ship would made about two complete trips per year. Marine Officers could apply to travel either aboard a US Navy transport or aboard commercial liners. Other travel opportunities saw Marines reaching Asia on exclusively chartered passenger ships, such as the 6th Marines who had several elements on the SS. President Grant, when a potential conflict with Chinese nationalists near Shanghai dictated the need for quick reinforcement from the states. Others, particularly officers requested and were occasionally granted, approval to reach or return from China through Europe via the Trans-Siberian Railway. Surprisingly, Marines continued to utilize the Russian route even after the 1917 Russian Revolution. Although with the outbreak of World War II in Europe, August 1939, HQ USMC finally prohibited the route’s further use.

The movement itinerary from the last full draft of China Marines, spring 1940

Additional points should be made regarding the movement of Marines to and from China. Occasionally, USAT ships would travel directly to China, particularly after the Army began maintaining a presence in Tientsin. In addition, the Chinese ports the USS Henderson and USS Chaumont would visit could vary from time to time. Lastly, a number of individual seagoing Marines completing their cruise aboard Asiatic Fleet ships might find themselves sent home on US naval warships that were scheduled to return stateside.

What was it like to be on the trip across the Pacific? A lot depended on your rank or just what level of hardship you were exposed to prior to making the crossing. James Jodan, a Private who left Mare Island for the Philippines and ultimately China, on board the USAT Sheridan in 1910, wrote she was a fine ship and the men played cards, put on a play and sang songs for amusement. He also included a portion of a ditty one Marine composed during the trip:

It was the good ship Sheridan,

The year was 1910

We sailed for Honolulu with a great big bunch of men

Some slept in three hammocks, some slept on the deck,

Some slept in places you’d think they would break their necks.

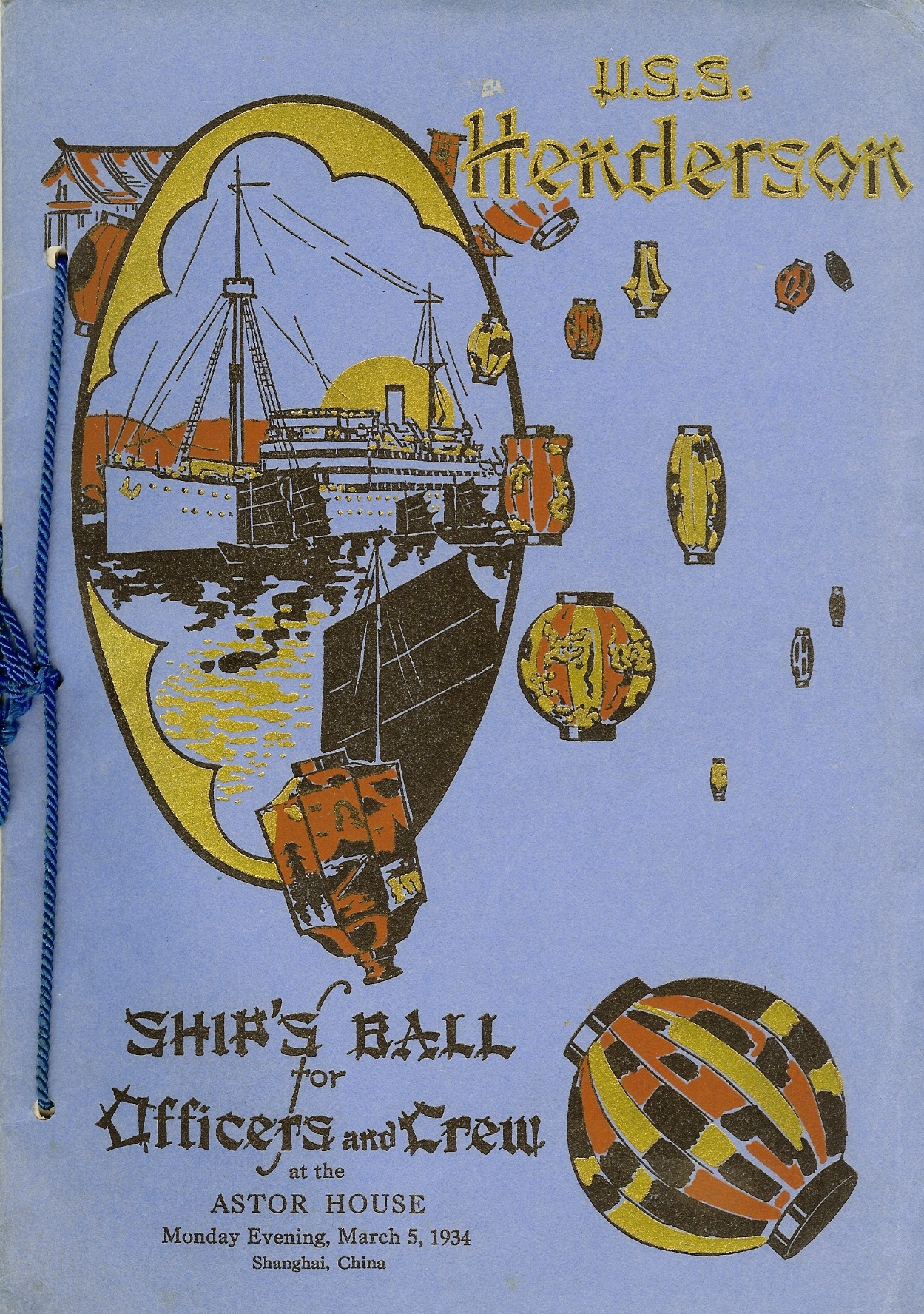

The USS Henderson

Luggage tag from the USS Henderson

Another pleasant story came from Mrs. Sallie Lytle, the spouse of Chief Pay Clerk John Lytle, a Marine officer assigned to serve at the American Legation in the 1930’s, while aboard the USS Henderson:

“It is beautiful this morning. The flying fish are playing all around our ship…I didn’t get seasick and have been enjoying excellent meals. We have movies every night, band, radio, and dancing….there are three bunks in our stateroom, running water, two desks and plenty of drawers to put things in.”

Now contrast Sallies’ tale with Pvt Leonard Dombroski's 2006 remembrance of his China crossing:

“Oh, the ride on the Chaumont was awful. I was seasick all the way to Pearl Harbor, but after that no more. We only had one afternoon in Hawaii for leave before we continued on to China. The ship was very crowded. They gave you only one bucket of water to wash up with. Space was so tight that when you turned over in your bunk you would hit the guy next to you. I think the bunks were four or five high. Below decks the ship smelled bad. I choose to just go up and sleep on the deck. One night I woke up in the rain and water was sloshing all around me but I thought what the heck I can’t get any wetter so I stayed on the deck. That was the only time that happened. There was not much to do on the ship. I think they made us stand watch us just to keep us busy.”

Sailors and Marines relax aboard the USS Chaumont mid-Pacific

Line-Crossing Ceremony Certificate. Awarded to Sailors and Marines who crossed the equator (latitude 000'00"). Over the years these certificates came in many shapes and styles. This particular example was pre-printed in a leather-bound photo album, allowing the owner to remove it and have the correct data filled in following his ceremony. Courtesy of the Pusel family Collection

Ships Program, USS Henderson

As for meals, Marines officers traveling aboard a Navy transports might dine on “Fried Lynnhaven Oysters” and “Roast Princess Anne Turkey" accompanied by fresh asparagus flamandes and “Potato Lorette.” Enlisted men, according to Chester Biggs, had their much simpler rations served on the open deck of the ship in assembly line fashion. Furthermore, Biggs and his fellow Marines were restricted to consuming their meals in any space on deck that didn’t draw the ire of the ship’s crew….a constantly repeated phase issued to a seated Marine was “Marine you can’t sit here.” At least the enlisted men could enjoy the same movies as the officers, when at night, weather permitting, a screen was erected on the deck of the ship and the men could gather around to watch. On most crossings a smoker would be held which featured boxing matches and entertaining acts by the ships passengers and crew. Another source of amusement was the time honored tradition of the “Crossing the Line” ceremony that was always held when the ship crossed the equator. I would like to close this section with a final detail about Pvt Fred Leach, who we met at the top of the page firmly declaring he would never ride on the USS Henderson again. In February of 1940, when Leach’s China Cruise was up, the Government chose to send him home aboard … the USS Henderson!

Marines preparing to disembark north China c. 1920