This section covers the foreign military forces the China Marines were likely to encounter during their China cruise. Prior to 1900 only seagoing Marines would have briefly interfaced with these soldiers and sailors during port calls at Hong Kong, Shanghai, treaty ports along the Chinese coast or Yangtze River. But with the permanent assignment of Marines ashore after the Boxer Revolt, the dynamic changed. Marines were now in daily contact with military forces from Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Italy, Austro-Hungary and Japan in a space one mile long by one half mile wide. In addition, Belgium and the Netherlands also maintained a small military presence in Peking as well. Although art work produced in China after 1900 proclaimed all the foreign powers as allies, stemming from their cooperation during the Boxer threat, they were in reality anything but friends. As such, instant friends or enemies could be created as a result of competition between each of these powers. Such fights became an unofficial extension of national polices, such as when Austrian Marines smashed an English owned movie house in Peking during WWI. During the same period French and English soldiers brawled with their German counterparts in the streets of the same city. Most of these fights were usually restricted to fistfights, but sometimes an occasional knifing would claim lives. The Marines were not immune to such brawls, as The Leatherneck magazine noted during WWI, before American entered the war, a German sentry seeing American Marines fighting with British soldiers, abandoned his post so he could assist the Marines in their fight. Jodan stated the Russian Guard force always supported the Marines if a opportunity presented itself. A fight between the Americans and Italians in Shanghai resulted in the loss of life and restrictions on both parties, that kept the clubs off limits for a period of time. This resulted in a serious loss of business for the club owners. Simultaneously though, friendships could quickly develop between Marines and indivduals from other nation's guard forces. It could be said the Marines over the length of their time in China held no long-term grudge against any one nation.

Austro-Hungarian Empire: Austrian Marines had the responsibility for defending their country’s legation. A 1913 intelligence report shows the strength of their contingent as four officers and eighty men. At the end of WWI they were withdrawn from China.

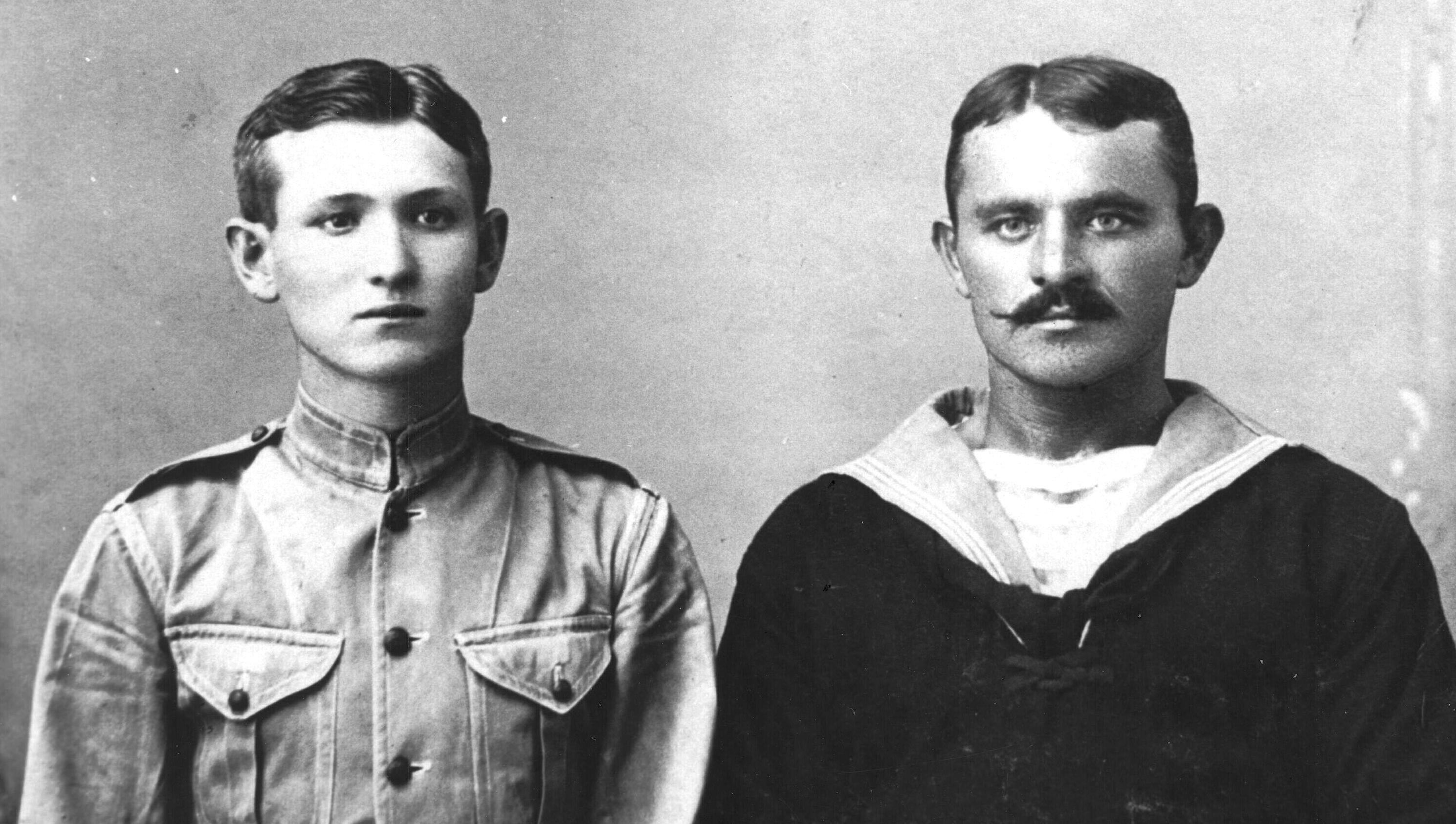

Marine Pvt Powell Smith with an Austrian Marine, c 1905-06. (Photo courtesy of the Powell Smith family collection)

Belgium: The Belgians maintained a 30 man garrison through WWI.

Great Britain: At the beginning of the Twentieth Century Great Britain, of all the foreign powers, had the greatest degree of influence in China. As such, it had a strong interest in expanding access to Chinese markets, while restricting others from gaining similar advantage. Britain maintained a colony in Hong Kong, dominated the economic life in Shanghai and along the Yangtze River. In Peking, the British retained, as a result of the prominent role they played in suppressing the Boxer Revolt, the senior position among the Legation Guards. Not only did they have the largest contingent of men, 13 officers’ and 376 men in 1913, but they also played a key role in orchestrating planning for the defense of the Legation Quarter. Furthermore, following their long tradition of promoting sporting and shooting competitions, Britain was the leader in organizing a number of such events for all the nations legation guards. The British guard in Peking taught the Marines ice hockey, while in Shanghai they introduced the Americans to rugby. As a globally influential power, many British colonial traditions were imported from India into China. Pidgin English was adopted from the Indian colony, as well as the tempo of the social schedule maintained by foreign diplomats. Following WWI, Britain slowly reduced its military presence in Peking to a single company, allowing the Americans and Japanese to become the largest players in the Foreign Quater. Unlike other nations legation guards, Britain rotated its guard force among various regiments. On the ability of the British and Americans to get along, initially, both sides clashed, with Jodan reporting the British and French always tried to jump single Marines when they could. But that hostility gave way over time as the two nations drew closer together. From the 1920’s on it was a sign of honor and friendship that a departing British Guard regiment might sometimes be allowed to pass through the Marine compound in formation and under arms, while the Marines would line the route in salute. Chester Biggs wrote of the final departure of the British guard in the summer of 1940 with the whole Marine Guard force lining the street offering a salute.

France: Responsibility for manning the French Legation Guard fell to the troops of the French Colonial Infantry. Their guard force was a mixture of French and Annamite soldiers. In 1913 French guard strength stood at seven officers and 230 men. Prior to the Marines arrival in 1905, there had been some serious fighting between the American Army Legation Guard and the French. The Frenchmen carried bayonets off duty, which lead to a number of stabbings. This stopped however when the guard force of other nations began allowing their troops to be similarly armed while on liberty. This lead to an agreement among the foreign troops that no one would be so armed. Several years later, Jodon witnessed a Frenchman jump a young Marine Field Music at a bar. The Marine, who happened to have been a boxing champion of some type, quickly knocked the Frenchman down several times before the Marine tired of beating the man, walked away. In the early Thirties French soldiers and Marines brawled at a Peking movie theater when the Frenchmen became enraged over Hollywood’s negative portrayal of one of their countrymen in the movie being shown. Yet despite these conflicts, the French allowed the Marines the use of their artillery range in Tientsin when the Marines conducted their annual heavy weapons qualification.

Germany: The reputation of the German Legation Guard suffers from the fact America fought two world wars against Germany. Because most China Marine memoirs were recorded after these wars, their remembrances were prejudiced against the Germans. However, during the period between 1905 and 1914, Marine relations seemed very harmonious with the Germans throughout China. Pvt Harvey wrote positively of his visits to German warships and in Peking the German post office was the preferred location to send China Marine mail home prior to WWI. Furthermore, the Germans were responsible for defending a sector of the Tartar Wall that sat next to the Americans, so a working bond was formed as well. And of course there was the well known story as noted above of a German guardsman leaving his post during WWI to assist the Americans in a brawl with English soldiers. In 1913 the German Guard force was recorded at 5 officers and 111 men. At the start of WWI the bulk of the German Legation Guard was withdrawn to their colony at Tsingtao to assist in its defense. The Germans must have created a new legation guard force drawn from its remaining staff, and other German nationals with military experience living in Peking. These men were interned by the Chinese when they declared war on Germany 1917. With Germany’s defeat in the war, their legation guard was permanently withdrawn.

Italy: The Royal Italian Navy had the responsibility for guarding the Italian Legation. Their strength was listed at eight officers and 95 men. The Italians were known to have dominated the international sporting competitions in the late 1930’s, as they hand-picked their finest athletes from all over their armed forces for assignment to Peiping, to ensure victory.

Japan: No nation suffered a more extreme shift in perception than how the Marines viewed Japan over the first forty years of the Twentieth Century. During the Boxer Revolt and many years afterward, Marines and sailors of the US Navy praised the Japanese for their professional skills, ferocity in battle and dedication to mission. Several Marines or their spouses even expressed a belief that a more vigorous and dynamic Japan should one day rule all of China. But as time went by, and Japan’s intentions toward China became increasingly obvious, the Marine’s attitude hardened. Although the Chinese had been warning for some time, and a number of US diplomats and senior Marines saw clearly what was coming, it really was not until 1937 that the average Marine could no longer ignore the fact that Japan and the United States were headed toward a clash in Asia. Desiring to build an Empire similar to its European counterparts, Japan slowly eliminated their rivals for domination of Asia: China in 1895, Russia in 1905, then Germany in 1918. Following the First World War, only Britain and the United States remained serious competitors. Of course like the impression of Germany after World War I, Japan’s legation guard was not remembered fondly following the Second World War. Brooke Astor claims her father Major John Russell, during a dinner at the Japanese Legation noted the dinner service had already incorporated a symbol of a captured Manchuria into its design- almost twenty years before it actually happened. Simultaneously, Jodan stated he rarely saw Japanese soldiers alone on liberty in the city, and if present were accompanied by a NCO. Furthermore, during a visit to the American compound Jodan noted a Japanese soldier tried to examine one of the Marines rifles. In the 1920’s and 30’s reports were submitted by various members of the Marine Guard claiming harassment by Japanese troops, but most of these claims were dismissed as non-issues. Although the Japanese did not participate in many of the sporting and shooting events hosted for the international guard force, they did participate in a number of defense drills and planning exercises with their foreign counterparts. But as Japan began its conquest of China, and increasingly pulled back from its Legation “Allies”, the Marines now turned their attention to collecting information on Japanese activities and capabilities. George Howe remembered as the Japanese overran Peiping in 1937, he was quickly sent to Chinwangtao to observe Japanese troop movements around the port. Col Price of the Fourth Marines, in turn worked closely with American newsmen to gather data on the Japanese activities around Shanghai. During the late 1930’s a barrier grew between the American and Japanese troops as both sides struggled to avoid a conflict with each other. Chester Biggs noted upon his arrival in Peking during the spring of 1940 “We would see the Japanese soldiers around town, but we just avoided each other.” By late 1941 the Japanese provoked a series of incidents involving Marines to Biggs words “get us out of the city.” When conflict did come on 8 Dec 1941, Biggs noted “The Japanese who captured us were garrison troops, not front line soldiers, so many of us didn’t really think much had changed. Things didn’t seem too serious to some of the guys. We could move around the compound with some restrictions. It wasn’t until we got to Shanghai when the guards started hitting us with their rifles that we saw how serious the situation really was. These Japanese troops had been fighting the Chinese for years.” For the majority of the Japanese Legation troops in Peiping, hate did not come quickly toward their American counterparts, instead it was a learned skill, developed through war. Yet looking back on Japanese women years after the War, author Richard Mckenna, himself a China sailor noted the Americans favored Japanese women and truly enjoyed their company and companionship, far more than any other Asian people. With the start of the Cold War, Japan was increasingly looked upon again with favor by the majority of Americans serving throughout Asia. The wheel had come full circle. Of the Japanese guard force in 1913, Lt Col Dion Williams recorded the strength of the Japanese Legation Guard at 12 officers and 295 men. By the mid 1930’s the Japanese Legation Guard consisted of a permanently assigned Headquarters Company and two infantry companies that rotated on a yearly basis. Each of these rotating companies was drawn from various Japanese infantry regiments.

Netherlands: The Dutch maintained a small thirty-five man garrison in Peking up through WWI. They were the only Great Power whose Legation Guards did not integrate in the Legation Quarter’s common defense plan.

Russia: How the Russian Legation Guard was remembered was damaged following WWII by the fact most China Marine histories were recorded during the Cold War when America and Russia were rivals. Prior to the Russian Revolution American Marines had a very good opinion of the Russian Legation Guard. Russian soldiers supported Capt Myers famous attack on the Tartar Wall during the 1900 siege of Peking. Years later Brooke Astor spoke in wonder of seeing the Russian Cossacks "tearing accross their parade ground hanging by one foot from the saddle to pick up a sword with their teeth." Jodan noted the American Marines often hosted Russian Guard members and engaged in good natured sporting events resulting in gifts being exchanged and the Russians given socks and other small clothing items their own government failed to provide. The Russians would reciprocate these small acts of kindness by coming to the defense of any Marine who may have been caught by a group of British or French Guards while on liberty. In 1913 the strength of the Russian guard force was six officers and 291 men. At start of WWI the Russians withdrew their entire guard, except for three or four men and an officer. Late in the war, the Marines occupied the old Russian barracks while the new West barracks was being built. Following the war Russia renounced their concessions, the need to station troops in Peking, and permanently withdrew its guard force. Strangely, despite the frictions caused in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution between America and Russia, Marine officers were still permitted to transit Russia en-route to the States until the start of WWII.

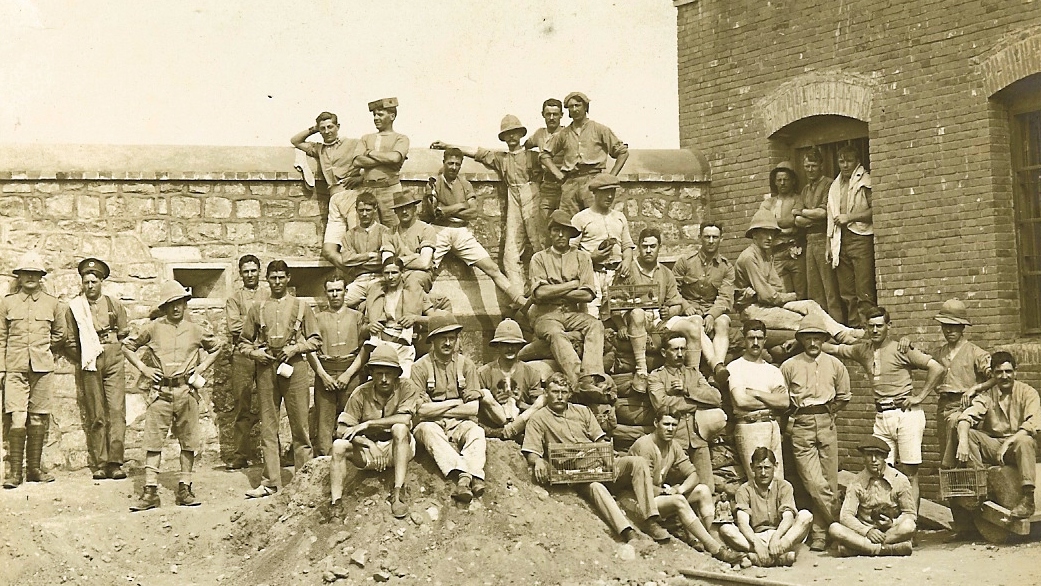

Marine, Belgium, Russian and Japanese Legation guards mix during the 1911 4th of July celebration at the Marine Compound

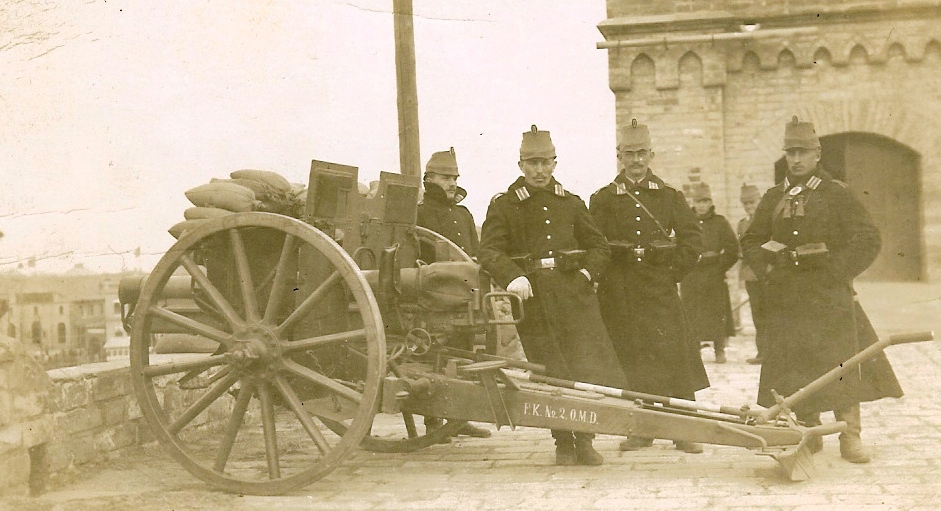

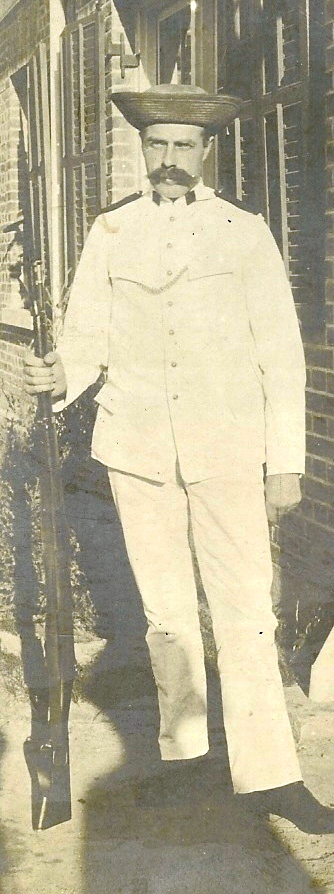

It was customary, each Spring, for the Allied officers (and sometimes the NCOs) to pose for a group picture. The setting was almost always at the British Legation. The photo above dates from 1912, while the photo below from 1907-08.